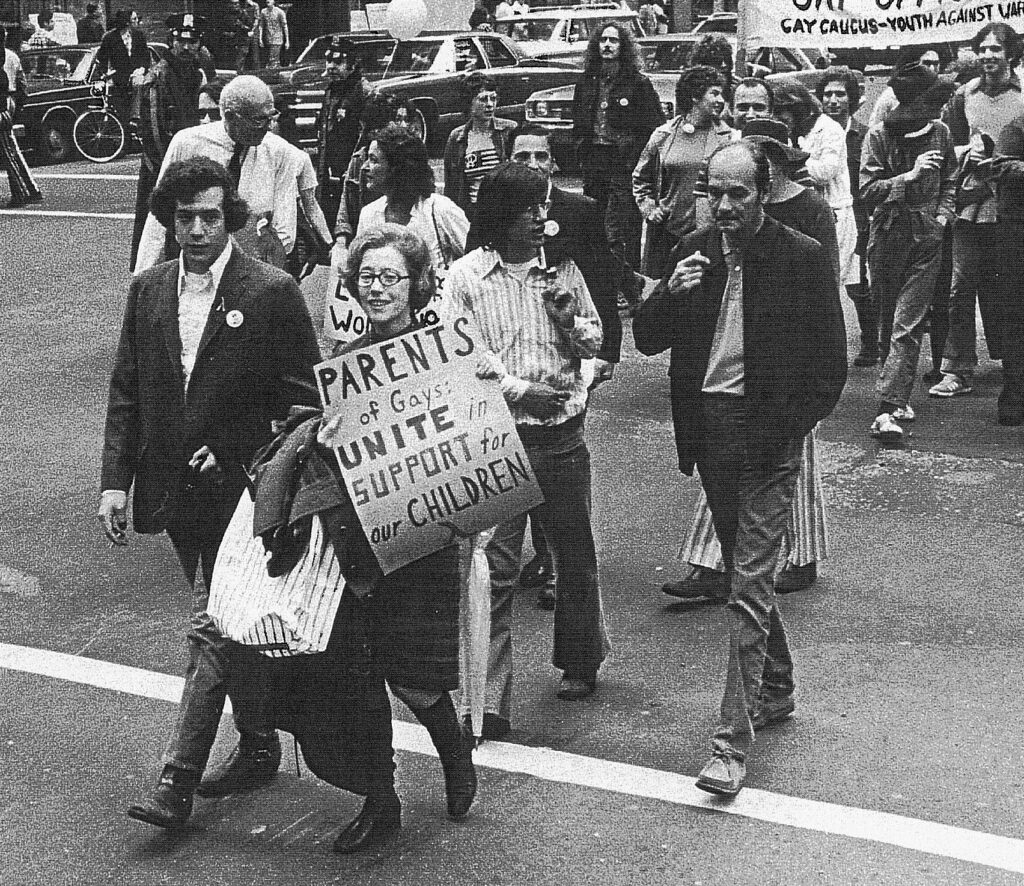

The idea for PFLAG began in 1972 when Jeanne Manford marched with her son, Morty, in New York’s Christopher Street Liberation Day March, the precursor to today’s Pride parade. After many gay and lesbian people ran up to Jeanne during the parade and begged her to talk to their parents, she decided to begin a support group. The first formal meeting took place on March 11, 1973 at the Metropolitan-Duane Methodist Church in Greenwich Village (now the Church of the Village). Approximately 20 people attended.

In the next years, through word of mouth and community need, similar groups sprang up around the country, offering “safe havens” and mutual support for parents with gay and lesbian children. Following the 1979 National March for Gay and Lesbian Rights, representatives from these groups met for the first time in Washington, DC.

By 1980, PFLAG, then known as Parents FLAG, began to distribute information to educational institutions and communities of faith nationwide, establishing itself as a source of information for the general public. When “Dear Abby” mentioned PFLAG in one of her advice columns, we received more than 7,000 letters requesting information. In 1981, members decided to launch a national organization. The first PFLAG National office was established in Los Angeles under founding president and PFLAG LA founder, Adele Starr.

In 1982, the Federation of Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, Inc., then representing some 20 groups, was incorporated in California and granted non-profit, tax-exempt status. In 1987, PFLAG relocated to Denver, under President Elinor Lewallen. Also in the 1980s, PFLAG became involved in opposing Anita Bryant’s anti-gay crusade and worked to end the U.S. military’s efforts to discharge lesbians—more than a decade before military issues came to the forefront of the LGBTQ movement. And by the late 1980s, PFLAG began to have notable success in organizing chapters in rural communities.

In 1990, following a period of significant growth, PFLAG employed an Executive Director, expanded its staff, and moved to Washington, DC. Also in 1990, PFLAG President Paulette Goodman sent a letter to Barbara Bush asking for Mrs. Bush’s support. The first lady’s personal reply stated, “I firmly believe that we cannot tolerate discrimination against any individuals or groups in our country. Such treatment always brings with it pain and perpetuates intolerance.” Inadvertently given to the Associated Press, her comments caused a political maelstrom and were perhaps the first gay-positive comments to come from the White House.

In the early 1990s, PFLAG chapters in Massachusetts helped pass the first Safe Schools legislation in the country. In 1993, PFLAG added the word “Families” to the name and added bisexual people to its mission and work. By the mid-1990s a PFLAG family was responsible for the Department of Education’s ruling that Title 9 also protected gay and lesbian students from harassment based on sexual orientation. PFLAG put the Religious Right on the defensive, when Pat Robertson threatened to sue any station that carried the Project Open Mind advertisements. The resulting media coverage drew national attention to PFLAG’s message linking hate speech with hate crimes and LGBTQ teen suicide. In 1998, PFLAG added transgender people to its mission.

At the turn of the century, the national office of PFLAG began to also develop signature programs to support the chapter network and to raise the family and ally voice in the battle for equality. Programs like Cultivating Respect: Safe Schools for All, Straight for Equality, and the National Scholarship Program.

In 2014, the organization officially changed its name from “Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays” to just PFLAG. This change was made to accurately reflect PFLAG members, those PFLAG serves, and the inclusive work PFLAG has been doing for decades. The mission and vision of the organization were also updated to further streamline and modernize the language, making it inclusive of everyone in the PFLAG family, while recognizing and celebrating the tremendous diversity of PFLAG’s membership, the communities PFLAG currently serves and aims to serve in the future.